A Conversation between Dr. Iain McGilchrist and Dr. Àlex Gómez-Marín

Wednesday January 19

9:00am PST | 12:00pm EST | 5:00pm GMT | 6:00pm CET

Science as we know it is a relatively recent human invention.

After the ‘scientific revolution’ of the seventeenth century, science and philosophy remained entangled as ‘natural philosophy’ until they started to separate in the nineteenth century (the very word ‘scientist’ was coined in 1834). Subsequently, science morphed from an activity carried out by wealthy people as a hobby (the ‘amateur,’ in the etymological sense of the word) into a paid job within an institutionalized system (the ‘professional’). Paradoxically or not, great ideas come more easily from people who are not paid to have them—it’s like forcing someone to be free, or compelling creativity by an act of will.

In the last decades, a series of technological and societal changes have further accelerated mutations of what it means to be a scientist; from the selection forces cast by neoliberalism on ‘scientific careers,’ to the kind of ‘science in the age of selfies’ that social media promotes. Scientists too are prey to the perverse dynamics of nowadays ‘attention economy.’ To understand what scientists do and why they do it, one must also understand the political and social contexts in which they live.

In addition, the rise of ‘big science’—initially in physics (particle physics and astronomy), and subsequently in life and mind sciences (genomics, and connectomics)—is reconfiguring the landscape typically inhabited by the romantic figure of the lone scientist receiving visions in dream-like states of consciousness and, eventually, advancing science in a stroke of genius. In turn, the idea of the scientist bred in the current academe is that of a diligent caffeinated deluxe technician as a part within the larger mechanism of research group army; a person trained exquisitely (and almost exclusively) on a research aspect, a specialist unable to keep track of what goes on beyond the narrow confines of his/her discipline. Young scientists are indeed trained to be good at following rules and procedures (explicit laboratory protocols, but also implicit codes of conduct and metaphysical commitments) but discouraged to learn to see when and how to transcend them.

In turn, the more recent promises of ‘big data’ and ‘artificial intelligence’ posit a near-future landscape where some of the core skills and tasks traditionally attributed to humans may be soon carried out by machines (or so the ‘scientific soteriologists’ claim). Algorithms are not just ingenious means to an end that require human intervention to imbue them with meaning, but are swiftly becoming ends in themselves, pretending they offer an automated unbiased interpretation of the data.

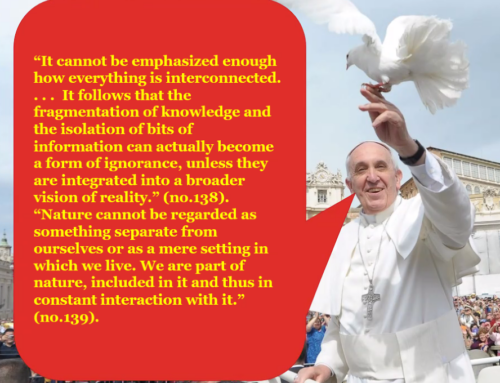

A re-appraisal of the habits of the modern scientist entails an ethical dimension as well: why do we treat animals as objects (as means, rather than ends in themselves), why do we study life in laboratories primarily by killing it, and why do we study life in laboratories in the first place? These questions also reflect on ecological considerations regarding our place in nature (humans in relationship with other animals, and other kingdoms of life) and our destruction of the planet. Francis Bacon’s prophetic vision of the Promethean scientist, so vividly captured in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, has become both a cautionary tale and an inspiration.

In addition, and despite the real ‘paradigm changes’ in physics at the beginning of the twentieth century, other branches of science such as biology and neuroscience remain under the spell of philosophical promissory materialism. Research facts are sold in tandem with covert metaphysical commitments. The objective-subjective divide still puzzles both scientists and the layperson. The mind-body problem remains to be solved (or dissolved).

In sum, the whole enterprise seems to be committed to suppressing broad thinkers, promoting academics that look more like corporate managers, PR mavericks and professional fund-raisers and less like scholars, who are asked to inhibit their interest in philosophy, and to cast suspicion on their fertile imagination. Dogma and habit are inhibiting free inquiry.

It is as if science as a whole is becoming less scientific.